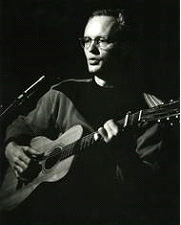

RETIRED EVERETT CARPENTER

NOW HAMMERS OUT FOLK SONGS

By Julie Muhlstein Herald Columnist

Bob Nelson gets up early. By 4 a.m., he's often at work in his home office, which has so much equipment it looks like a recording studio. At 72, he's making good on a promise.

Bob Nelson gets up early. By 4 a.m., he's often at work in his home office, which has so much equipment it looks like a recording studio. At 72, he's making good on a promise."It's a promise I made to myself years ago," said Nelson, a folk singer who lives in Everett with his wife, Judy.

I visited Nelson on Wednesday to see in person what keeps him so busy. He had sent e-mail explaining his efforts: "I started learning, collecting and singing folk songs when I was 13," he wrote. Now retired from his work as a carpenter, Nelson has time to devote to preserving the music he loves.

"I'm converting over 300 reel-to-reel tape recordings from analog to digital CDs. I also have over 400 cassette recordings," he said. "It's a long process. I've been at it seriously about five months, and have burned up four tape recorders."

Past meets future at Nelson's house, where shelves are loaded with boxes of old tapes. He also has a treasure trove of vinyl records, and a turntable to help him save the Northwest's vintage folk music for future generations.

He has yet to find a proper repository -- a university, library or music organization -- for the archives he's creating, which also include short biographies Nelson is writing about performers. "My goal is to preserve this material so that 50 or 100 years from now, some future researcher will have these songs available," he said. "Otherwise, they will die with me."

Traditional folk music is alive in his heart, and it's a big part of his history. In the 1950s and '60s, Nelson was caught up in the spirited folk scene in Seattle's University District. He performed around the region at hootenannies -- he calls them "hoots" -- jam sessions, coffeehouses and college concerts.

Back then, Nelson would haul with him a 60-pound Webcor reel-to-reel tape recorder, capturing performances of folk legends and obscure artists. "It was a working tool, that reel-to-reel. I'd take it to a hoot, then listen and practice," he said.

Nelson was an original and active member of the Pacific Northwest Folklore Society, founded in 1953 by the late Walt Robertson, Don Firth and others. In recent years, Nelson, Firth and Stewart Hendrickson have revived the Pacific Northwest Folklore Society (www.pnwfolklore.org). The group has sponsored folk music performances at the Everett Public Library and other venues.

"I'm having a lot of fun," said Nelson, who in 2007 recorded "Songs I Sing After Dark," a CD collection of traditional songs that includes "The Old Settler," the Ivar Haglund ballad that was printed on Ivar's restaurant place mats.

"I had basically hung it up for about 40 years while I was making a living and being a father," Nelson said of singing and performing. He's been happy to reconnect with artists he knew years ago. Today's folk scene "is very active," he said.

Although Nelson was among the founders of the Northwest Folklife Festival, he said he won't be at this weekend's event. Held annually over Memorial Day weekend at the Seattle Center, the festival has grown too big and too far from its roots for Nelson's taste. "I avoid it like the plague," he said.

That's not to say Nelson hasn't rubbed shoulders with folk music giants. The night Joan Baez played at the Seattle World's Fair in 1962, Nelson said Baez and a friend didn't want to stay at a downtown hotel. They ended up in the Seattle home of Nelson and his first wife, he said.

And Pete Seeger? "I talked to Peter about two weeks ago," Nelson said of the 90-year-old folk legend.

At home in Everett, Nelson feels blessed to have played a part in the Northwest's folk legacy. He's proud of himself for learning computer skills needed to save the music -- the songs of David Spence, Bill Higley, Walt Robinson and many more. "I was a carpenter and folk singer, and I had to become a techie," Nelson said.

He figures that compiling CDs, cross-indexing songs performed by several singers, and writing biographies will take at least two years.

"We don't want the music to die with us," Nelson said. "I can't die till it's done."

Julie Muhlstein: 425-339-3460, muhlstein@heraldnet.com.