HONOR THE TRADITION

What singer-songwriters (and other contemporary folk musicians) need to know

by Stewart Hendrickson

HONOR THE TRADITION

What singer-songwriters (and other contemporary folk musicians) need to know

by Stewart

Hendrickson

Music builds on tradition.

Sometimes the tradition evolves gradually, other times big jumps are taken. We

have all been exposed to different types of music in our past. How we treat

this musical history, build upon it or change it, delve deeper into it or

ignore it, has an important effect on our growth as musicians.

Tradition can be thought of as

something fixed in time and structure, or it can be something that changes or

evolves over time. Should we regard traditional music as set museum pieces, or

should we use it as a stepping-off point for our own music? If the latter is

our choice, how do we proceed? How do we honor those who have gone before?

First, we need to be aware of the

tradition. Many first and second generation Americans rediscover the ethnic

music of their parents and grandparents, sometimes after initially rejecting it

as too old-fashioned. Often this happens when they have children and realize

that they have an ethnic background that needs to be passed down. Or someone

may ask them about their own ethnic music, and they realize they have no

answers.

Cookie Segelstein is a klezmer

violinist I met at the American Festival of Fiddle Tunes in Port Townsend many

years ago. She is first-generation American, her parents were holocaust survivors

from Eastern Europe. But Cookie was born in Kansas City, and grew up in an environment

as far from her ethnic heritage as possible. “I had no Jewish friends, dated no

Jewish boys, and stopped going to synagogue after my bas mitzvah. I wanted

nothing to do with this world of pain. I studied music, received a Master’s in

Music from Yale, and became a working classical musician. I eventually married

a non-Jewish man.”

Then she had her first child.

“All that I had turned away from, the richness of tradition, my father’s

history, and especially the music of the Jewish people all of a sudden became

the most important thing in my life besides my child. I called my folks daily

with questions. What were the names of all who perished? What was the klezmer band like in their towns? How do you make cholent?”

She realized that she was a critical link in this tradition and wanted to pass

it on to her own children. She became more active as a klezmer

violinist to the point of it taking over her classical career, and is now most

comfortable expressing herself in her own ethnic culture.

One of the exciting things about klezmer music is that it is continuously evolving. Eastern

European Jews carried the klezmer tradition to

America, mixing with and picking up elements of American popular and jazz music

in the early 20th century. It almost died out, but was rediscovered by a new

generation of Jewish youth in the 1970’s, and underwent a tremendous revival.

It fused with other musical traditions, and our current music is much richer

because of it.

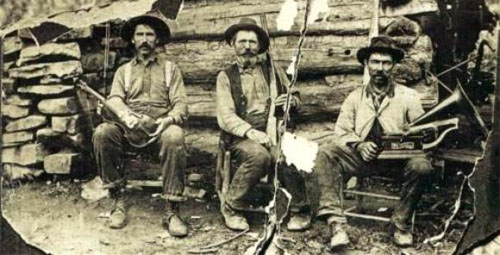

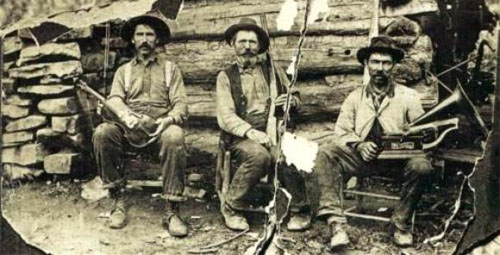

The folk revival of the ‘50s is

another example of building upon the tradition. The immediate carriers of this

tradition were people like Woody Guthrie,

Lead Belly (Huddie Ledbetter), and Pete Seeger. But it goes back before that

to people like John and

Alan Lomax, Frank and

Ann Warner, and others who were collecting music from Appalachia, the South

and other places, and recording the traditional musicians before their music

became lost in the urbanization of America.

During the folk craze of the

‘60s, the rural roots of folk music changed. The authenticity of rural people

singing of their hardships, simple pleasures and protests was lost in a new

generation of urban singers.

A new type of folk music evolved

around the urban environment – phony trios singing pseudo-traditional songs

more akin to Tin Pan Alley, Vietnam war protest songs, and the new singer-songwriter

genre. Many of these songs are good, but they are far removed from the tradition.

Others were more commercial pop and have mercifully disappeared.

Irish music was introduced into

popular American culture by such groups as The Clancy Brothers and

Tommy Makem, The Dubliners, and The Chieftains. This music later

fell under the heading of “Celtic Music.” The term “Celtic” encompasses the

people of Ireland, Scotland, Wales, Cornwall, Isle of Man, Brittany, Northumbria, and Galicia. This term has lost most of its

meaning (who knows what kind of music the pre-historic Celts made?), and is now

just a marketing label.

Like American folk music, Irish

music has lost much of its traditional roots. Its revival in Riverdance took it to a commercial level that would be

unrecognized by the traditional musicians of old Ireland, and it lost much of

its tradition and charm.

Some musicians, however, have honored

the tradition while still allowing their music to evolve to higher levels in

different ways. Kevin Burke of

Portland and Martin Hayes formerly of

Seattle grew from their Irish roots to become two of the most respected Irish

fiddlers in the world. Their music has stayed within the tradition, but has

also brought the tradition to a new level of playing and interpretation.

It might seem strange to mention Bob Dylan in this regard, but however you

regard him in other ways, he was quite aware of tradition and used it to evolve

his music to a level some would not regard as folk music. Dylan went to England

early in his career to hear traditional songs from which he got material for

his future songwriting. He also mined traditional Scottish tunes and songs from

his association with Jean Redpath during their early Greenwich Village days in

New York. From this he got the following tunes: Bob Dylan’s Dream (Lord

Franklin), Girl of the North Country

(Scarborough Fair), Farewell (Leaving of Liverpool), and A

Hard Rain’s Gonna Fall (Lord Randall).

Bob Dylan’s borrowing from traditional

lyrics is evident in his song Tomorrow is

a Long Time. It comes from a 16th century poem, Westron Winde – Westron Winde, when will thou blow / The smalle raine downe

can raine / Christ, if my love were in my armes / And I in my bed again – which he changed to: Yes, and only if my own true love was waitin’ / Yes, and if I could hear her heart a softly poundin' / Only if she was lyin’

by me / Then I’d lie in my bed once again.

There are “next generation” folk

musicians who have strong family backgrounds in traditional music and have used

these to enhance their music. I recall hearing The Mammals play at the Northwest Folklife

Festival in 2006. They represented 2nd or 3rd generations of some of our

well-known folk singers: Tao

Rodriguez-Seeger, grandson of Pete Seeger; Ruth Unger, daughter of Jay

Unger; and others. They shared the stage with Jay Unger and Molly Mason for the

Benefit Concert. They were well received, but afterwards I heard some old

folkies grousing that they “just weren’t traditional.” Well no, they weren’t

traditional, but they did have respect for the tradition. They just put it in their

own folk-rock style and sound. They took the old songs and tunes and made them

their own, with respect and knowledge of what went before. I enjoyed it – they

were different. The Mammals have since disbanded and the members have gone

their own separate ways.

Another example is Eliza Carthy,

the daughter of Martin Carthy and Norma Waterson, who grew up immersed in her

parents’ world of English traditional music. “Describing herself simply as a ‘modern

English musician’ Eliza Carthy [at age 39] is only

now beginning to reach the height of her musical powers. During a 20-year

journey/career she has become one of the most dazzling and recognised

folk musicians of a generation. She has revitalised

and made folk music relevant to new audiences and has captured the most

hardened of dissenters with canny, charismatic and boundary-crossing

performance. Many of the current crop of young professional folk musicians owe

their successes in part to her determination, standard-bearing and campaigning

spirit.” Some of her music is ‘far out,’ but when she sings a traditional song

it is exciting to hear her new take on it and at the same time her respect for

the tradition. Recently Eliza and her father produced their first ever duo

album together, The

Moral of the Elephant, with a new and different take on traditional

songs. Here Martin

and Eliza talk about producing this album. And here

is an Eliza Carthy playlist.

Another “next generation” folk

musician, Jeff Warner grew up

listening to the songs that his parents Frank and

Ann Warner collected during their field trips through rural America. He is

the editor of his mother’s book, Traditional

American Folk Songs: From the Anne and Frank Warner Collection, and

producer of the two-CD set, Her Bright

Smile Haunts Me Still, the Warners’

recordings of rural singers, many of them born in Victorian times. He continues

these traditions as a master folklorist, traditional singer, instrumentalist

and storyteller. He plays concertina, banjo, guitar and several “pocket”

instruments, including bones and spoons, and “he inhabits a song in a way which

few singers can do” (Royal Oak Folk Club, Lewes, UK). Here are some of his performances posted on the web.

Jeff will perform for the Seattle Folklore Society on

Saturday, Oct. 25 – don’t miss him! “This concert will include a live

multi-media presentation about his parent’s song-catching through rural

America, followed by Jeff performing songs, banjo tunes, 18th-century New

England hymns, and sailor songs.”

Tim O’Brien is not a “next generation”

folksinger, but growing up in Wheeling, West Virginia, he was surrounded by

classic country and bluegrass music. He also learned the traditional American mountain

ballads and fiddle tunes. He is described by Mark Knopfler,

in whose band he has performed, as “a master of American folk music, Irish

music, Scottish music – it doesn't matter; a fine songwriter and one of my

favorite singers.” “Over the years,” Tim explains, “my music has become a

certain thing. Each time I go into the studio to make a new album, I could make

an Irish record, or a bluegrass record, or a country record…but it seems

artificial to sift anything out. I feel like I’d be leaving out something

important. In the end, I just try to make it round… I’m a folk musician,” he

says humbly. “I gravitate towards the old sounds and I still sing a good bit of

traditional material. My songs come out of that well of folk music. If you do

it long enough, you can’t always tell the old from the new – it blends

together. It becomes what happens between the chicken and the egg: I don’t know

which came first, but it contains the whole of life.” Tim is a master

instrumentalist and plays guitar, fiddle, mandolin, banjo and other instruments

– his musical hero is the late Doc Watson. To appreciate his wide range of

musical talents watch a two-hour video of

his concert at the historic Whately Congregational

Church in West Whately, MA, on July 17, 2013.

These artists represent just a

few of the many folk musicians who continue to honor the tradition in their

music, even though it may evolve far from those roots. Their songs seldom mention the

words “I” and “me,” but they tell stories of interesting people, places,

historical times and recent events. They continue the traditions of the old ballads,

songs, and tunes into contemporary times.

We need to honor the tradition as we develop our own music. Tradition is not static, but continues to evolve. William Blake

(1757-1827) wrote “The difference between a bad artist and a good one is the

bad artist seems to copy a great deal; the good one really does copy a great

deal.”