Reprinted with permission from FolkWorks March-April 2017

Mildred: What’re you rebelling against, Johnny?

Johnny: Whaddya got?

~ Marlon Brando in “The Wild One”, 1953

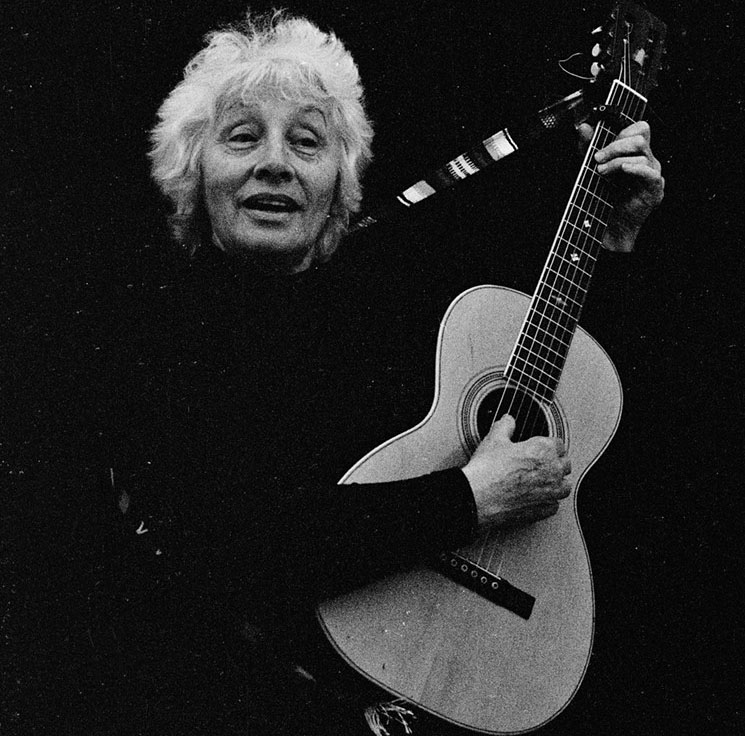

Marlon Brando’s reply to Mildred’s question suits Malvina Reynolds to a T: but unlike Johnny in The Wild One, Singer-songwriter Malvina Reynolds (August 23, 1900—March 17, 1978) was a learned rebel. She got her Ph.D. the old-fashioned way—she earned it, in the UC Berkeley English Department in 1938. She never used it to teach, however, because her first act of rebellion was to refuse to sign the California loyalty oath when she was accepted for a teaching position at Berkeley. Faced with Robert Frost’s life-changing choice at the fork in the road she took the one less travelled by—“of whom it could be said: She was an artist, and a red.” (MR)

Her rebellious songs reflect not only a thoughtful but an educated mind, one that transformed her knowledge into the art of song. It is nowhere on better display than in her trenchant anti-propaganda song No Hole in My Head. She opens with

Everybody thinks my head’s full a-nothin’

Wants to put their special stuff in

Fill the space with candy wrappers

Leave out sex and revolution

But there’s no hold in my head

Too bad.

Her song has given me much comfort over the years—and a powerful defense against many people—both friends and strangers—who seek to fill my head with their “special stuffin’.” Most recently it has been about such pseudo-archaeological discoveries as The Lost City of the Monkey God. I never replied to the many emails inviting me to various events (a movie, a TV appearance, a live book signing, and a radio interview) with the author and filmmaker involved in this project, but had I done so, it would have been brief: I don’t believe in God, not the Jewish, nor Christian, nor Monkey. I do resolutely believe in the First Amendment right of all people to believe in any god or gods they want to, and not to bother me with their beliefs. Unfortunately, in Los Angeles especially, everyone seems to insist on their right to waste my time.

Malvina died on March 17, 1978, during Women’s History Month (the month of International Women’s Day, March 8). What better time to celebrate her life as a rebel songwriter, scholar and political activist? She began her journey to the center of the left with a slow but steady stream of songs she kept sending to Pete Seeger in Beacon, New York—from her home on Parker Street in Berkeley, California. Her first songbook was thus entitled, The Muse from Parker Street. Pete’s first responses were not enthusiastic, “One more weekend painter,” he figured—except she was a songwriter. But the songs kept coming and her persistence paid off. It finally dawned on Pete that his reactions were saturated with male chauvinism—she was a female Woody Guthrie, sending him enough songs to fill a book. He started publishing them in People’s Songs, his little periodical that predated Sing Out! Then Harry Belafonte began to notice her, and decided to record one of them—it was her classic song of parental bereavement at not noticing that your child had grown up before your eyes: Turn Around. Before she knew it, she was sitting on a hit—the Limelighters then recorded it and she was off and running. A few years later Pete found one that suited him, and her paean to nonconformity, Little Boxes, became one of the signature songs of the decade of social change.

Turn Around Little Boxes

All the while she was making her own records as well—on Pete’s label Columbia Records. They weren’t necessarily hits, but they fed the folk singers of the time with the best and most pointed topical songs they could find—right up there with Phil Ochs and Tom Paxton and the early Bob Dylan—before he stopped writing “finger-pointing songs.” Malvina kept on pointing her finger—at injustice and the Ku Klux Klan (The Battle of Maxton Field), at nuclear testing and environmental depredation (What Have They Done to the Rain?), at war (A Brief History of Warfare and We Hate To See Them Go), and at the atrocities of industrial capitalism (I Cannot Sleep). But like Woody she also wrote children’s songs (the acutely observed You Can’t Make a Turtle Come Out) and lullabies (Morningtown Ride) and very much unlike Woody—whose heroic autobiography Bound for Glory celebrated himself every bit as much as Whitman’s Song of Myself—Malvina became the voice of the anti-hero, the disinherited and the disenfranchised who refused to give up (I Don’t Mind Failing In this World). Malvina Reynolds was the champion of the underdog who discovered her own heroes in the most unlikely of places: The Little Mouse and The Little Red Hen. What a refreshing voice she was! Never self-aggrandizing, and rarely gloomy, she looked at the world through her own eyes and as Winston Churchill said, “When you’re going through hell, keep going.”

Her very personal secular religion was a powerful tonic to the bromides of the self-congratulatory major faiths:

On Monday I think I’m a sinner

On Tuesday I think I’m a saint

On Wednesday I don’t know what I may be

But I know that a saint I ain’t:

(Chorus)

Somewhere between the good and the evil,

Somewhere between the right and the wrong,

Somewhere between the kind and the mean,

Somewhere between is where I belong.

She accepted her fallen condition without bemoaning her fate. And to those who thought they had hit bottom—such as my anonymous comrades in a well-known 12-step program—she was a constant reminder that There’s a Bottom Below.

Unlike her fellow folk celebrities Joan Baez and Judy Collins she had no advantages from either her looks, her voice, or her youth. Since she didn’t become even modestly successful until she had turned 60 (having been born—like Louis Armstrong—at the turn of the Century in 1900) she welcomed her role in the nickname her fans bestowed on her: The Singing Grandmother. It gave her a kind of freedom that many other performers didn’t have—she had no grandiosity or show business role to fulfill—her only hallmark was the power of her songs and the sheer brilliance of what she had to say. Her always surprising perspectives shone new light on the well-traveled roads from which she departed—she wrote a beautiful song about the earth as seen from outer space, marveling at how small we are in comparison to the universe. From Way Up Here, the earth was in good company in Malvina’s song—just like her Little Red Hen and Little Mouse and her children’s songs—it inspired a new kind of affection from its very lack of imposing size—a perfect antidote to mankind’s hubris.

From a popular women’s magazine of the 1950’s she pulled together this gem: “It says in Coronet Magazine, June, 1956, page 10, that married women are not as happy as women who have no men / married women are cranky, frustrated and disgusted / While single women are happy and free / creative and well-adjusted.” “We Don’t Need the Men / Oh we don’t need the men / We don’t need to have them round / Except for now and then / They can come to see us / When they’re all dressed up with a suit on / Otherwise they can stay at home and read about the Dodgers—We don’t care about them / We can live without them”—and then she steps outside her own feminist critique—“But they look cute in a bathing suit on a billboard in Manhattan!” That is quintessential Malvina—creating a dialogue from the dialectic of her own experience, always making a point that is more complex than the usual social observations of mass culture—even when she uses mass culture to articulate it. She was a wife and mother (whose daughter Nancy Schimmel is a songwriter and performer in her own right), as well as a feminist and social critic—and found a perspective that embraced them all. Once again, she always saw with her own eyes. But like a great dramatist she could inhabit many voices: Her love song to her husband William “Bud” Reynolds, a carpenter and labor organizer whom she married in 1934, embodies his own working class voice, declaring: Bury Me in My Overalls.

I have sung her children’s song Magic Penny at more fundraisers than I can count; in typical Malvina style she lets the smallest unit of currency carry the ball for the much larger sums we hope to raise: “Love is something if you give it away / give it away / give it away / give it away / Love is something if you give it away / You’ll end up having more.”

Malvina Reynolds was a rebel with a cause, and created the best known anthem for civil disobedience we may ever see; Pete Seeger included it in his legendary 1963 Carnegie Hall concert that Columbia Records released as We Shall Overcome: It Isn’t Nice:

It isn’t nice to block the doorways

It isn’t nice to go to jail

There are nicer ways to do it

But the nice ways always fail

It isn’t nice / It isn’t nice

You told us once

You told us twice

But if that is freedom’s price

We don’t mind

—and here she riffs into an extended jazz vocal solo:

We don’t mi…i…i…i…i…i…i…no…no, no, no…we don’t mind…

So to anyone out there whose ears are bombarded with unwelcome advice and predatory gurus new and old, who wants to listen with their own ears and see with their own eyes, I leave you with the last verse of Malvina’s great song of Emersonian self-reliance, No Hole In My Head: “So please stop shouting in my ear / There’s something I want to listen to / There’s a kind of birdsong up somewhere / There’s feet walking the way I mean to go / And there’s no hole in my head / Too bad”

So how would this quintessential leftwing populist topical songwriter stand up in this new age of right wing and alt-right “populism”? We don’t have to wonder, or speculate; Malvina has already spoken, and she is no less relevant today than in 1974, when she added her voice to the chorus of students fifty years her junior: “They’ve got the world in their pocket / pocket, pocket, pocket / They’re got the world in their pocket / And they’re up there in control / They’ve got the world in their pocket / They can shake it they can rock it / They can kick it for a goal / They’ve got the world in their pocket / But their pocket’s got a hole.”

Malvina Reynolds was old when I was young, and now that other post-sixties radicals are (lucky if we are) old, she remains forever young. And as she wrote in one of her earliest songs,

Sing along! Sing along!

And just sing la la la la la if you don’t know the song

You’ll quickly learn the music, you’ll find yourself a word

Cause when we sing together we’ll be heard.

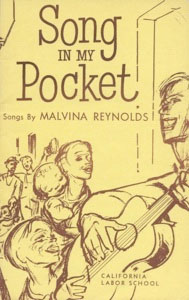

This sure-fire set opener was printed in 1954, in Malvina’s very first charming, rare song pamphlet, which I got as a gift from my fellow folk singer and old leftist Lenny Potash: Song In My Pocket, published by the California Labor School in San Francisco. It’s a pamphlet much like Tom Paine published in 1776—Common Sense and The Crisis—where he wrote the immortal line,“These Are the Times That Try Men’s Souls.” We are living in times like these again, where a songwriter like Malvina Reynolds could inspire a whole new generation to stand up, speak out and sing truth to power.

This sure-fire set opener was printed in 1954, in Malvina’s very first charming, rare song pamphlet, which I got as a gift from my fellow folk singer and old leftist Lenny Potash: Song In My Pocket, published by the California Labor School in San Francisco. It’s a pamphlet much like Tom Paine published in 1776—Common Sense and The Crisis—where he wrote the immortal line,“These Are the Times That Try Men’s Souls.” We are living in times like these again, where a songwriter like Malvina Reynolds could inspire a whole new generation to stand up, speak out and sing truth to power.

Unfortunately we’ll never hear what Malvina might have sung about our new “all power corrupts but absolute power corrupts absolutely” President—but she would have written the most razor-sharp song out there. And in her absence, how can we keep from singing?

[Editor’s note: readers may be interested in a 2016 article in the OC Weekly about Malvina’s time in Southern California: The Life and Times of Malvina Reynolds, Long Beach’s Most Legendary (and Hated) Folk Singer.

Also Love It Like a Fool: a 1977 doc film on folksinger Malvina Reynolds.]

Ross Altman has a Ph.D. in English. Before becoming a full-time folk singer he taught college English and Speech. He now sings around California for libraries, unions, schools, political groups and folk festivals. You can reach Ross at Greygoosemusic@aol.com. All Columns by Ross Altman